Rosemary Goudreau: When the circus comes to town, you go

from: sun-sentinel.com

By Rosemary Goudreau

May 25, 2014

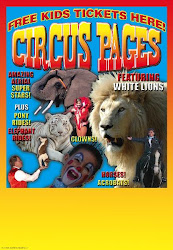

Every year in January, when the circus comes to town, South Florida media members are bombarded with emails from animal rights extremists: Boycott the circus! Tell your friends to boycott the circus, too! They abuse animals!

This year the deluge was so pervasive — harassing, really — that while better sense dictated otherwise, I responded to one spammer saying: "If I get one more of these emails, I'm not only going to go to the circus, I'm going to tell all my friends to go, too."

Truth is, I like the sights and sounds of the big top — the clowns, the acrobats and the show-stealing animals.

And because I once had a front-row seat to meet those who work with the animals, I welcomed the recent news that the long-running lawsuit against Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus had been settled, with those who've made unproven claims of animal mistreatment paying nearly $16 million.

A few years back when I was working for myself, I took a gig writing the playbill bios for all the Ringling Bros. performers in Zing Zang Zoom. At the circus' winter home outside Tampa, I met everyone from the lion tamer, to the high-wire walkers, to the two human cannonballs.

"It's as dangerous as it looks," said one cannonball. "The first big thing is just to get in there. Second is to get in the right position to come out. ... You don't think about what could happen. You just think about what you have to do."

I came to believe the circus is a family and that a special bond forms between the trainers and their animals.

The zebra lady was particularly memorable. Zebras are skittish by nature and always ready to bolt. But after dinner some nights, she'd go sit with them in the corral. Remarkably, they'd sometimes curl up next to her and sometimes, even roll on their sides. "I've built the trust with them," she said.

Then there was the dog trainer who kept every dog he ever trained. "These dogs are my life, my job. When you work with them every day of your life, they become part of your family."

The elephant trainers, too, sounded like proud parents.

"We went on a four-day vacation once and couldn't wait to get back," one said. "The entire time we felt like we were without some of our kids."

"The elephants listen better than my kids," added his wife.

Some elephants have been with Ringling for more than 50 years, and the trainers' references to family rang true. After all, why would people abuse animals whose spirit and gifts are needed for their livelihoods?

History tells us some elephant trainers have used cattle prods and other abusive techniques, but if such mistreatment is still happening, I suspect it occurs at fly-by-night circuses. From having asked countless questions of Ringling trainers, and knowing about the company's conservancy for older elephants near Sarasota, I never believed the nation's biggest and best circus mistreats its elephants, as was suggested.

In the end, the critics could prove no wrongdoing. Indeed, they were found to have paid a former barn helper almost $200,000 to make his claims, which the judge said undercut his credibility.

So while the animal rights movement has its place, if extremists bombard me when the circus comes to town again next January, I will be forced to share with friends a Southern maxim of life.

That is, when the circus comes to town, you go.

Rosemary Goudreaus is editorial page editor,South Florida Sun-Sentinel